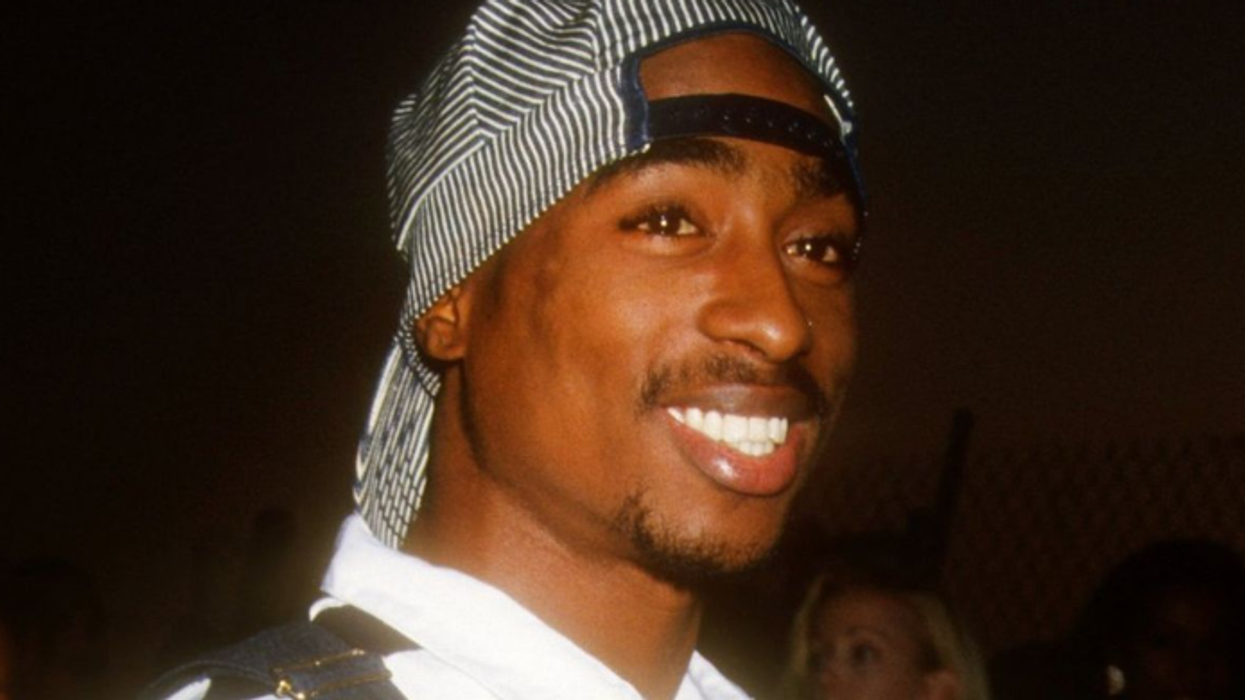

The Confession That Shook Hip-Hop: Keefe D Reveals the Chilling Details Behind Tupac Shakur’s Murder

:sharpen(0.5,0.5,true)/tpg%2Fsources%2F62a272d3-db41-4c22-918a-3d3ad63acc74.jpeg)

For 27 years, the murder of Tupac Shakur remained one of the most enduring enigmas in hip-hop history, a tangled web of gang rivalries, East Coast-West Coast beefs, and shadowy conspiracies that captivated fans and investigators alike. Tupac, the charismatic rapper whose lyrics blended raw street poetry with profound social commentary, was gunned down in a drive-by shooting on the Las Vegas Strip on September 7, 1996. He succumbed to his injuries six days later at the age of 25, leaving behind a legacy of albums like All Eyez on Me and a void in the music world that echoed through generations.

Theories abounded—ranging from involvement by his rival The Notorious B.I.G. to government plots—but concrete answers eluded authorities. That silence was shattered when Duane Keith “Keefe D” Davis, the last surviving occupant of the car from which the fatal shots were fired, came forward with a detailed confession. In police interviews, a memoir, and public statements, Keefe D laid bare the plot, from a alleged million-dollar bounty to the split-second decisions at a red light that altered music forever. His account, chilling in its specificity and corroborated by police evidence, paints a picture of gang loyalty, revenge, and opportunistic violence.

To understand the confession, one must revisit the volatile backdrop of 1990s hip-hop. Tupac Shakur, born Lesane Parish Crooks in 1971, rose from a troubled youth in East Harlem and Baltimore to become a West Coast icon after signing with Death Row Records in 1995. Under the mentorship of label head Marion “Suge” Knight, Tupac’s output exploded, but so did the tensions. The East Coast-West Coast feud, fueled by media hype and personal slights, pitted Death Row against Bad Boy Records, led by Sean “Diddy” Combs and his star artist, Biggie Smalls.

A pivotal flashpoint was the 1995 Source Awards, where Knight infamously dissed Combs onstage, declaring, “If you don’t want the owner of your label on your album or in your video or on your tour, come to Death Row.” Tupac escalated the beef with his scathing 1996 track “Hit ‘Em Up,” where he mocked Biggie and claimed to have slept with his wife, Faith Evans. According to Keefe D, this diss “pissed [Combs] off,” transforming business rivalry into a deadly vendetta.

Keefe D, a high-ranking member of the South Side Compton Crips, positioned himself at the center of the storm. In his 2019 memoir Compton Street Legend and a 2008 police interview (granted immunity for drug charges), he alleged that Combs approached him with a proposition during a meeting at Greenblatt’s Deli in Los Angeles. “Man, I want to get rid of them dudes,” Keefe D quoted Combs as saying, referring to Knight and Tupac. The price: a $1 million bounty to “wipe their ass out quick.”

Keefe D, seeing an opportunity for his gang to profit, agreed, though he later claimed the South Side Crips only received partial payment after the hit—$50,000 upfront via an intermediary named Eric “Zip” Martin, with the balance never materializing. Combs has vehemently denied these allegations, calling them “pure fiction and completely ridiculous” in a 2018 statement to L.A. Weekly. Nonetheless, Keefe D’s narrative frames the murder not just as gang retaliation but as a commissioned assassination, blending street code with high-stakes music industry intrigue.

The events of September 7, 1996, unfolded like a tragic script, beginning with a night of celebration that devolved into chaos. Mike Tyson, a close associate of Knight’s, was fighting Bruce Seldon at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. Tupac, fresh off a performance high and riding with Knight in a black BMW 750iL as part of a Death Row convoy, attended the bout. Keefe D and his crew—fellow South Side Crips including his nephew Orlando “Baby Lane” Anderson, Terrence “Bubble Up” Brown, and DeAndre “Big Dre” Smith—were also in town, adhering to a gang tradition of attending Tyson fights. What started as a routine evening escalated when Anderson, a 22-year-old Crip with a reputation for toughness, crossed paths with Tupac’s entourage in the MGM lobby.

The spark was a prior incident: months earlier, a Death Row affiliate had allegedly snatched a chain bearing a Death Row medallion from Travon “Tray” Lane, a Mob Piru Blood (allied with Death Row), at a Foot Locker in Compton. Spotting Anderson—whom they believed responsible—Tupac and his crew ambushed him in the casino. Surveillance footage captured the brutal beatdown: Tupac landing the first punch, followed by Knight and others stomping Anderson as he curled on the floor.

Humiliated and bloodied, Anderson retreated, but the assault ignited a firestorm. Keefe D recounted learning of the attack while at the MGM café: “Tupac, Suge, and them Death Row niggas jumped on my nephew Baby Lane. The shit became ominously personal.” Vowing revenge, the group armed themselves. Zip, the intermediary, provided a .40-caliber Glock pistol, stashed in a secret compartment in the armrest of their white Cadillac. “It’s time to get the money,” Zip reportedly said, tying the weapon to the bounty.

The seating arrangement in the Cadillac, as detailed by Keefe D, proved fateful. Bubble Up drove, positioning the car for mobility. Keefe D rode shotgun in the front passenger seat, ready to act if needed. In the back, Big Dre sat behind the driver, his massive 6’6″, 370-pound frame dominating the left side. Baby Lane occupied the rear right seat, closest to where Tupac’s BMW would pull up. This configuration, Keefe D explained, sealed Tupac’s fate: “When we pulled up, I was in the front seat. If they would have drove on my side, I would have popped them.” Instead, the back seat offered a clear line of fire.

After arming up, the group headed to Club 662, a Knight-owned venue where Tupac was slated to perform at a Death Row afterparty. They waited over an hour, but the targets didn’t show. Frustrated, they drove off toward the Strip. Fate intervened at a red light on East Flamingo Road, near Koval Lane. A car full of women spotted Tupac in the adjacent BMW and screamed his name, prompting him to pop his head out the sunroof. Keefe D’s crew, hearing the commotion, made a quick U-turn and pulled alongside. It was a chance encounter, not a meticulously planned ambush. Knight, at the wheel of the BMW, looked “terrified,” Keefe D recalled.

Tupac, reaching under his seat—possibly for a gun—froze as the Cadillac’s rear window lowered. From the back seat, shots rang out: four bullets from the Glock, striking Tupac in the chest, pelvis, hand, and thigh. Knight was grazed in the head. The Cadillac sped away, ditching the car blocks later. Back at their hotel, they celebrated with champagne, treating it like “another day at the office.” Tupac’s death was “collateral damage,” Keefe D wrote coldly, though he later expressed remorse: “I have a deep sense of remorse for what happened to Tupac. He was a talented artist with tons of potential.”

The aftermath was a labyrinth of stalled investigations. Orlando Anderson, long suspected as the triggerman, denied involvement before his own death in a 1998 Compton shootout. Bubble Up was killed in 2015, and Big Dre died of a heart attack in 2004, leaving Keefe D as the sole survivor. His 2008 confession to LAPD detectives, captured on tape, provided the breakthrough: “One of my guys from the back seat grabbed the Glock and started bustin’ back.” He adhered to “street code,” refusing to name the shooter explicitly, but implicated Anderson indirectly. Police corroborated details through witnesses and ballistics—the .40-caliber matched casings at the scene.

Keefe D’s revelations culminated in his arrest on September 29, 2023, charged with first-degree murder as the orchestrator. He pleaded not guilty, claiming his statements were exaggerated for profit. The case, however, has dragged on with multiple delays. Initially set for June 2024, the trial was postponed to November 2024, then February 2026, and most recently to August 10, 2026, amid a flood of new evidence described as “voluminous” by defense attorneys. Motions to suppress evidence from a 2023 home search—deemed unlawful by the defense—have been filed, though a judge denied a dismissal in January 2026. Grand jury testimony introduced twists, with one witness suggesting Big Dre, not Anderson, fired due to obstructed views from Dre’s size. Prosecutors argue Keefe D’s self-incriminating book and interviews provide ample proof.

The confession’s impact reverberates through hip-hop. Tupac’s murder, followed by Biggie’s in 1997, marked the end of an era, forcing the industry to confront its glorification of violence. Fans mourned a voice that championed the oppressed, while the feud’s resolution—through tragedy—underscored the senselessness. Keefe D’s details, from the bounty negotiations to the red-light roulette, humanize the horror: a nephew’s vengeance, an uncle’s opportunism, and a split-second that silenced a legend. As the trial looms, one truth endures—Tupac’s spirit, immortalized in tracks like “Changes,” outlives the bullets. Yet, Keefe D’s words remind us: in the streets, “real Gangsters are nothing to fuck with.”