“Are you ready to cry?”

The ticket-taker chuckles knowingly while checking our tickets at Landmark Theater. It’s 5:06 p.m. on Friday afternoon and we’re still catching our breath from the hurried bike ride over. This greeting is not what I expected — a scolding for our lateness maybe, or an advertisement for a bucket of overpriced popcorn (which we’ll accept, but that’s beside the point).

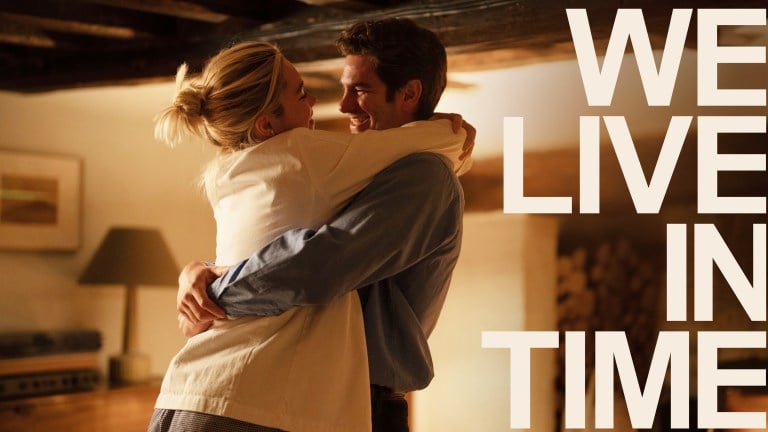

I can’t say I’m completely surprised. Here for the evening showing of “We Live in Time” — which opened in theaters on Oct. 11 — I’m ecstatic to watch Florence Pugh and Andrew Garfield — as passionate chef Almut and dorky Weetabix employee Tobias — fall in love. And I’ve done my homework. I’ve seen a few trailers for this movie and I trust its leading actors’ ability to evoke intensity in spidersuits and petticoats, corporate offices and Swedish communes. I fully expect the film to pack an emotional punch, but it still feels unusual that the ticket-taker would choose such an abrupt approach.

Five minutes later, I understand why. Before we’ve even opened our M&M’s, we’ve been hit with the story’s central problem: Almut and Tobias have something truly special, and there’s something terribly wrong. Almut is sick. Her future and their life together are not guaranteed. I can feel the energy in the theater change as we brace for emotional impact. We’ve just met these characters, but we’re devastated, stripped of the chance to watch their love unfold without tragedy.

But Pugh, Garfield and director John Crowley have something a little different in store. “We Live in Time” doesn’t go from one event to the next in a linear path. The eras in Almut and Tobias’ life are broken up and interspersed — a heartfelt moment with their young daughter stitched with an argument in the kitchen over whether they’ll ever have children. One moment they’re reluctantly parting after a perfect date in their early romance, and the next Almut is waking Tobias up with a bowl of freshly-made whipped cream in their countryside home.

Knowing where they’ll end up doesn’t preclude the joy we feel in watching the characters connect. While their chemistry is electric, Almut and Tobias’ love is wonderfully simple. Their start may be dramatic — Tobias stumbling into oncoming traffic in a divorce-induced daze — but their story isn’t made up of the typical rom-com staples. They don’t sprint through airports, kiss in the rain or declare their love in front of a hundred strangers.

Instead, they connect in the subtle, passing moments of ordinary life. They crack eggs, stroll through Herne Hill and host cozy dinner parties. At times they are awkward, other times angry and others perfectly content. Their moments, both trivial and momentous, occur alone with a natural ease and imperfection.

They discuss Almut’s treatment plan in the hospital parking garage while contemplating adopting and subsequently killing a dog for their daughter (I won’t try to explain this one, you’ll have to watch it yourself). In their candle-lit living room, Tobias struggles to speak and thus reads his marriage proposal from a small green notebook. They make detailed plans and then watch them go awry, traffic jams and broken locks creating messy, unpredictable scenes. In depicting this kind of love, Pugh and Garfield achieve what most films aim for but often miss in search of bold cinematic moments: They feel real.

Still, the beauty of this story cannot be separated from the pain of its circumstance. The jumbled timeline keeps the audience emotionally unstable, never allowing us to feel fully secure. Watching Almut and Tobias twirl joyfully on a carousel, we dread the darkness ahead. When it hits, we want desperately to go back.

In many ways, the experience as a viewer mirrors what the characters — and anyone who has experienced tragically limited time with a loved one — are feeling, even if it only scratches the surface of that pain. Knowing that time is finite and shorter than what could possibly be deemed fair casts a shadow of precious urgency over every moment. At the same time, experiencing such intense love and building a life together means that even in absence, the connection is never really lost.

What struck me, too, about the film is how it speaks to the nuance that accompanies such an impossible task as the one Almut is facing. Losing each part of her life also means losing each part of herself. Yet, her career, in which she excels and feels great passion for, her friendships, her beloved family and the simple moments that fill the gaps in her life ultimately give it color. The film makes no attempt to quantify these priorities or deem their relative significance. It’s all important, and it’s all allowed to matter.

Just as this realization settles, though, the movie is over. I won’t spoil the ending, but I suspect it’s where most people will feel unsatisfied. Truly, it isn’t satisfying or relieving; we crave more time with these characters and wish they had more time together.

The film ends unexpectedly and we’re left without enough. This metaphor sinks in deeply. When the credits roll, the theater heaves a collective sigh and no one moves for several minutes. In my opinion, it’s a perfect conclusion to a heartbreaking story.

When we finally walk out, the man at the counter sees our long faces and laughs a little. He warned us, and he was certainly right. The movie made me cry and laugh and want to tell people I love them. I think that’s all you could hope for.